|

Rotterdam

KLINGER The NetherlandsNikkelstraat 2 3067 GR Rotterdam

Elsloo

KLINGER Service Center LimburgBusiness Park Stein 208A 6181 MB Elsloo

Velsen-Noord

KLINGER The NetherlandsRooswijkweg 200 1951 MD Velsen-Noord

Moordrecht

Hadro TechnologySouth Lane 351 2841 MD Moordrecht |

The future of district heating: energy from wastewater

The role of industrial heat pumps in energy transition

17-10-2023, The future of district heating at Wien Energie, Austria

Austria's largest energy supplier, Wien Energie, is also shaping the future of district heating. Project manager Georg Danzinger is working with KLINGER on an installation with up to seven industrial heat pumps in Vienna. The heat energy is supplied by wastewater. But how exactly does this work?

The installation of the said heat pumps is taking place at the Ebswien wastewater treatment plant and is one of the most important projects for the Austrian energy supplier. Moreover, Georg Danzinger informs that it will be the largest plant using heat pump technology. The project, which is in its first expansion phase, is already using three industrial heat pumps sourced from French manufacturer Johnson. These three heat pumps already produce a thermal output of about 55 MW. Together with his team, Georg is developing projects that focus on making district heating CO2 neutral. Their goal is to implement sustainable heat generation in combination with renewable energy generation.

Energy from wastewater

Industrial heat pumps are crucial to taking the next step toward generating renewable energy. Using this technology, the company Wien Energie can extract heat energy from wastewater from the nearby main treatment plant, helping to make heat generation CO2 neutral. Georg explains the following: "In the first phase, we are installing three of the six industrial heat pumps, which together produce a thermal output of 110 MW. We even have room for a seventh heat pump. The water for district heating has an outlet temperature of 93 °C (199 °F)." This heat is delivered to a district heating network that distributes the heat to households and businesses in Vienna.

In winter, wastewater from the treatment plant has an outlet temperature of 11-12 °C (52-54 °F) and in summer the water reaches a temperature of 24-25 °C (75-77 °F). The higher the source temperature, the higher outlet temperature of the heat pump can be achieved. "This improves the COP (coefficient of performance), or efficiency of the heat pumps," explains the experienced project manager, who has also managed environmental impact assessments (EIA) for large projects.

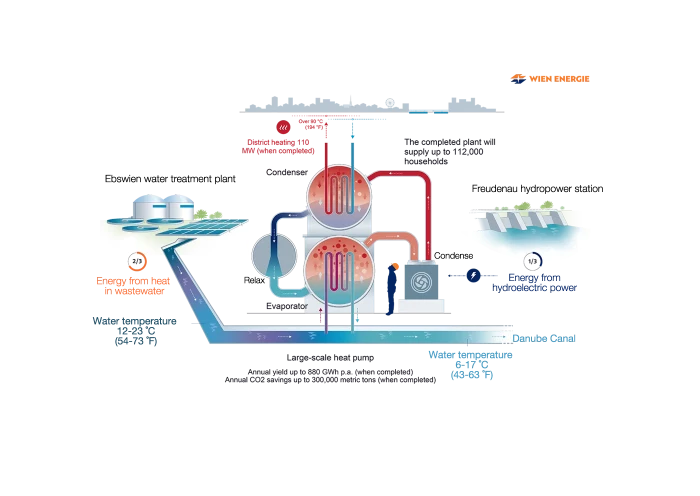

Infographic operation of heat pumps in district heating

Process at Ebswien

The heat pumps were made in France and transported in parts to Vienna.

The industrial heat pumps are scheduled to begin operation in January 2024. The infographic on the left provides a detailed overview of the entire process, from the water treatment plant at Ebswien and the power plant's energy supply to the operation of the heat pumps and the utilization of the heat for district heating.

Source of infographic: Wien Energie

District heating with 100 percent renewable energy sources

Whereas elsewhere wastewater is generally seen as a negative, it is not a problem here, as it offers significant potential. The heat pumps are not only an energy source that can be used for district heating, but also lower the temperature of the wastewater returning to the Danube, reducing the heating effect on the river.

But that's not all: the plant gets its energy for district heating from 100 percent renewable energy. This is thanks to a direct connection from the Freudenau power plant, where a third of the energy used comes from hydropower. The remaining two-thirds is extracted as heat from wastewater from the treatment plant. "So if you put in 1 kW of electrical energy, you get 3 kW of usable heat energy released," says Markus Fuchs, account manager at KLINGER Gebetsroither in Austria.

It requires real teamwork

Georg plans to commission the plant in the fall of 2023, with the heat pumps going into operation in mid-2024. During the planning phase, there were many details that kept needing clarification, as much with the manufacturer as with other suppliers, including KLINGER Gebetsroither. "We had to prove ourselves again in the construction company's pitch," Markus says. District heating is nothing new for Wien Energie, as the company has been responsible for the heat supply of Vienna for some 60 years.

The fact that he can rely on the excellent quality of these products also makes his job so much easier. Unlike other projects, there is no general contractor on this project. "We manage everything ourselves, although we also receive support from other departments at Wien Energie, such as Electrical Engineering and Control Station Engineering. And we are grateful for that," says Georg.

Control valves as a safety device

In total, the project cost around 70 million euros. The share of the costs of the KLINGER control valves within this amount was almost negligible. And yet they have a huge impact on the entire heat pump process. Because nobody wants to stand next to a leaking control valve, where hot water turns into steam in the atmosphere. When talking about the danger of leaking valves, the conversation quickly turns to media such as chemicals. But even though water vapor does not cause pollution, standing next to a leak is definitely not a good idea. Pressure and temperature are high and it's not "just" water. KLINGER offers sealants that are ideally suited for applications in district heating. Georg goes a step further and calls control valves a safety feature.

The future of district heating

Hydrogen and geothermal are hot topics, even at Wien Energie, especially when it comes to the energy transition, "but we'll save that for a future article," Georg says. Finally, he emphasizes that the future of district heating looks promising. With projects like this industrial heat pump plant, Wien Energie is showing that sustainable, efficient heat generation is possible. And with partners like KLINGER Gebetsroither at their side, they are well equipped to meet the challenges of the energy transition.

For more information about our district heating products and services, please contact: